"This exhibition is a great adventure in my life."

Finally, there is a Mesopotamian exhibition in Hungary, as this is where human civilization began, yet it often doesn’t receive the attention it deserves.

In the 21st century, among ancient cultures, Mesopotamia—primarily located in present-day Iraq—has suffered the greatest damage. In 2003, the Iraq National Museum was looted, and in 2014, terrorists from the Islamic State, stationed in Mosul, destroyed Assyrian palaces and smashed statues. This shocked the public and drew attention to the region. Archaeological excavations have resumed in Iraq in recent years with positive results, which could also spark interest in the area.

Several motifs from Mesopotamia, such as demons, appear in pop culture, in films, comics, and as amulets or tattoos that people wear featuring these figures. This includes the Tower of Babel, an eternal trope familiar from the Bible, which always seems to offer something new. And, of course, Mesopotamia is important to science: here at ELTE Faculty of Humanities, we have Assyriology courses, a Near Eastern Archaeology program at the Institute of Archaeology, and an ELTE excavation in Iraqi Kurdistan that has been ongoing for ten years. But I can’t think of many things in Hungary where the public would encounter Mesopotamia. It’s gradually being pushed out of public education as well. Now we had the chance to sneak it back in a little.

I was browsing online to see what Mesopotamian-themed exhibitions have been held around the world in recent decades, and I found a few. How familiar are you with these?

If we only look at the Old Continent, Europe, similar large-scale exhibitions, like the one in Budapest, take place roughly every 4-5 years. In 2008, there was an exhibition on Babylon that was first held at the Louvre in Paris, then moved to the British Museum in London, and finally to the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin. The latter also hosted an Uruk exhibition in 2015. Then, there was an exhibition on Ashurbanipal at the British Museum in London in 2018, and another on the Assyrians in Naples in 2019. Here in Central Europe, the Kunsthistorisches Museum held two exhibitions focusing on the Near East, one at the end of the last century and the other at the very beginning of the 2000s. Since then, there hasn’t been one in Central Europe. I am genuinely pleased that the Museum of Fine Arts' temporary exhibition now focuses on ancient Mesopotamia, allowing us to present the Assyrian and Babylonian world of gods and demons to the Hungarian audience and visitors to our country. You can read Zoltán Niederreiter's opening speech here.

How does the Budapest exhibition fit into this lineup?

I’ve visited nearly thirty Mesopotamian exhibitions in my life, and I’ve seen a wide variety of themes and approaches. Ours is unique in several ways. Primarily, it focuses on a specific period—the era of great empires, specifically the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires in the first half of the first millennium BCE. This Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian period is crucial; it marks the time of the first major Near Eastern empires, when large parts of the Near East came under the rule of one, then the other empire. This era is described in the Bible—think of Babylon and the Tower of Babel—and ancient authors also wrote about the stepped ziggurats, great kings, and vast cities. Thanks to the Mesopotamian excavations that began in the mid-19th century, more and more artifacts from that time, such as the remnants of palaces and temples with unique sculptural works, have come to light. There is also a vast corpus of texts—cuneiform inscriptions containing literary, historical, scientific, and other important writings.

And there are countless cylinder seals...

After 2008, I began focusing on cylinder seals because I wanted to work on a topic that simultaneously involves visual, material, and written sources. Cylinder seals are fascinating stone artifacts with depictions that, in certain respects, represent the highest standard of craftsmanship within this material culture, and many also bear inscriptions. They’re also mentioned in texts, but what’s most significant is that they provide the primary visual source group from this period, as they exist in large numbers and their depictions are incredibly rich, especially regarding the pantheon of gods. I noticed that while information about deities was fairly well collected from written sources, the visual sources and imagery haven’t been as thoroughly documented. Since 2008, I have studied various artifacts, mostly cylinder seals, in nearly 30 European, American, and Israeli museums and have documented over 1,000 of them.

You already had a large amount of material on your computer when you established the 'Lendület' research group, and one of your goals was to create a database from this material that could be used for further research.

Before the 'Lendület' project, I essentially had the complete corpus on my computer, which I estimated at around 5,000-5,500 items. I had just completed my first catalog of cylinder seals preserved in a Brussels museum, where I developed a classification system with 84 objects. This system was then used within the 'Lendület' framework to create a searchable electronic database of the entire corpus based on various keywords. This allows the material to be examined by collection, origin, raw material, dimensions, and the depictions on the seals. The visual elements can be further analyzed according to scenes, figures, symbols, and motifs. The project's first two years were essentially dedicated to processing the data from this corpus.

It was also my goal to publish the objects that had already been researched. Miklós Szabó, an academic who was my supervisor in the classical archaeology program, used to say that our primary task is to describe, classify, analyze, and publish unpublished sources, as the interpretation will be done and redone by others over time. The Bibliothèque nationale de France holds one of the world’s largest cylinder seal collections, and Louis Delaporte published its material in 1910. This catalog is still used today, but mostly for its illustrations. I didn’t want to reprocess this material; instead, I supplemented it with items that have been added to the collection over the past century. This resulted in a nearly 300-page catalog, which I compiled together with one of my MA students, and it will be published next year.

How did this become an exhibition? How difficult was it to organize?

From the very beginning of the project planning, I considered it important to organize a temporary exhibition centered around the world of gods and demons. This is what interests me the most, and it is also the essence of the Lendület project. To organize the exhibition, I first had to win over László Baán, the director general, who supported this project from the start, and then the curators from whom we wanted to borrow items. The heads of the major collections were familiar to me because I had either worked with them or conducted research at their institutions, and they were open to collaboration. Erika Roboz, a staff member of the Museum of Fine Arts, became the other curator; we worked together on the exhibition design, organizing the sections, themes, and the arrangement of the objects within them.

Many negotiations took place regarding the acquisition of the objects. Approximately 150 items arrived from, among others, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Louvre, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the NY Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. The exhibition features several objects that the respective institutions have never lent to anyone before; some have been lent out for the last time because their condition or the possible means of transportation no longer permits it, and one has not been published before and is included in our exhibition catalog for the first time.

Despite the conservation efforts, several objects are fragile and require special handling; some needed a crane for moving in, and a special path had to be constructed for their transportation within the building, as their weight exceeds one ton. Then there are also very small objects, which presented the challenge of how to make them accessible to visitors. The miniature images on the seal cylinders, which are just a few centimeters in size, had to be enlarged to make the narratives in their scenes visible. The world of gods, in fact, is most prominently represented here.

The exhibition is unique in that it focuses on divine and demonic beings, natural and supernatural forces, the visible and the invisible; no exhibition with such a theme has been organized anywhere before. How is the world of gods and demons represented in the rooms?

We established nine sections and assigned the objects to these. The introduction showcases the discovery of Babylon, focusing on the Ishtar Gate and the procession path lined with lion figures. We aim to help visitors understand the results of the vast archaeological enterprise that uncovered Babylon. Then follows the presentation of the historical background of the great empires, in which the main protagonists appear to be the kings, but we actually illustrate the kings' role in relation to the gods. The ruler is chosen and crowned by the gods; he acts in the name of the gods, leads military campaigns, builds temples for them, and provides for and serves the deities residing within.

Among the gods, Ninurta, a god of war, is the first to appear, who holds a role similar to that of the king in some respects. He was the one who restrained the flood or defeated the demon army of rocks, returning triumphantly to Mesopotamia afterwards. The next section focuses on nature, the stones within it, and the wildlife that inhabits it. We present the wild animals depicted on the seal cylinders, as well as the hybrid creatures made up of these wild animals, which lead us into mythology. This brings us to the marshland of southern Mesopotamia mentioned in the Babylonian creation epic, where the gods were believed to have been born.

We can also get to know their astral gods, such as the Sun, the Moon, and the Morning Star. We are already at the zodiac, a Babylonian invention that continues to live on as a legacy in European culture, which also includes Dürer’s engravings that help in understanding the celestial world. After presenting the natural gods, primarily Adad, the storm god, we enter a house where we showcase the world of demons and the protective beings against misfortune. Upon entering the palace, we encounter genies and divine beings in the grand palace reliefs. Returning to Babylon, we can learn about Marduk, the chief god, and the associated dragon serpent. For the presentation of the Tower of Babel motif, we follow ancient sources and then showcase Dutch paintings, followed by 20th-century Hungarian artistic and graphic works, the analysis of which was prepared by Diána Kulisz, an Egyptologist and art historian from ELTE. Additionally, there is a section of the exhibition where we evoke Babylon through cinematic works and Pazuzu, the most well-known demon, through examples taken from pop culture.

Transcendence interests everyone, and there are enough sources from this period to present the world of the gods. We can bring to life what they thought about the Moon in Mesopotamia and how they perceived the winds through illustrations or even incantations. We combined the sources. The most important objects for this are the seal cylinders, but there are also amulets, sculptural works, and, of course, cuneiform clay tablets.

The exhibition is genre-wise extremely colorful; alongside the objects, there are photos, drawings, paintings, as well as maps and minerals, creating a very diverse material that can even captivate children.

Yes, we paid great attention to the diversity of genres, just as we emphasized the use of colors and the play of light and shadow. Visitors enter a space with special lighting through the exhibition. For example, when we enter the house, it becomes darker, but in the light, the amulets appear, including the most famous creation of the Mesopotamian demon world, the so-called Hell Plaque. Pazuzu, the wind demon, is perhaps the most important figure in the demon world; he appears most frequently in pop culture and greets us at the entrance.

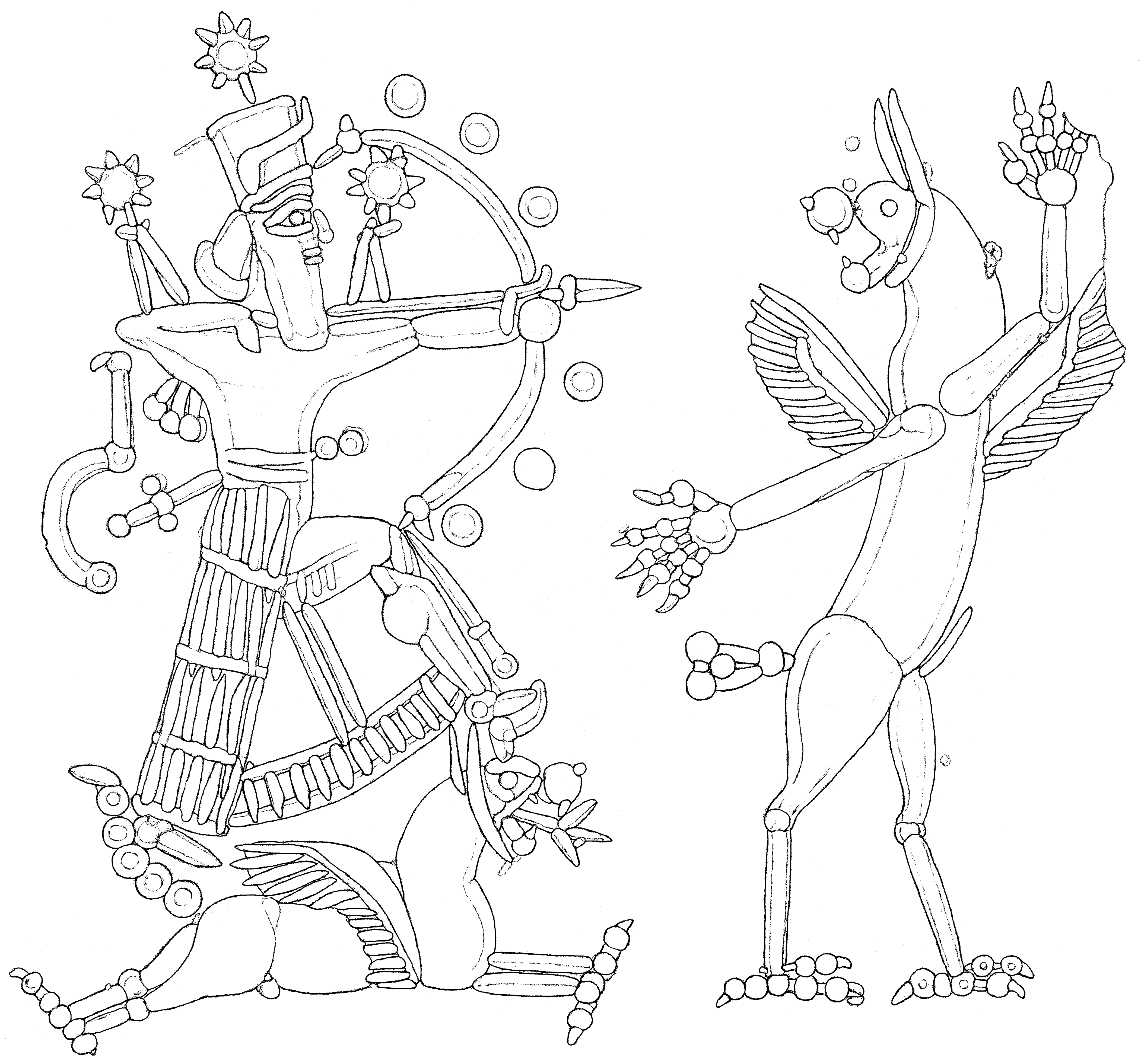

Children can also attend this exhibition. I’m very curious to see how the younger ones will react and what will captivate them. By the way, I have also created a coloring book from my drawings for them, complete with explanations; my own children have already tried it out.

You primarily study seal cylinders, and what you see during their examination you write about in your research. An exhibition, however, addresses a broader audience: to what extent does it reflect the original concept of the researcher?

Yes, I had a concept, but I had to realize that many of us work together on an exhibition—from the foreign lending collections, through the museum's graphic designer, to the person responsible for the lighting in the exhibition—and all the contributors add something to the original concept. This was not easy to accept. There were many themes that needed to be introduced somehow, and we had to find the tone and genre that would help visitors step into the next room a bit wiser after leaving the previous one. The theme of "The Kingdom of Gods and Demons" had to be brought to life in a given space, and its represented message had to be made understandable to visitors. This exhibition is a great adventure in my life.

Your research inspired the organization of the exhibition. But how did the exhibition contribute to your academic work?

It is a significant achievement on an international level that a 500-page exhibition catalog has been produced in English, which also has a Hungarian version. The volume contains many images and drawings and essentially covers the exhibition itself. But it offers more than that: it includes 48 studies written by 24 researchers from universities and museums in Vienna, Berlin, Budapest, Chicago, Leiden, London, Munich, New Haven, Paris, Rome, Toronto, Warsaw, and Washington. Thanks to their manuscripts, this exhibition catalog truly became international, and we hope to have showcased the diversity of the latest research related to the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian pantheon to our readers. Creating the catalog brought me great joy; I was able to fully realize my concept here, and the participants were partners in this effort, enriching my research through this work.

Some of the foreign participants took part in a workshop seminar held on October 17-18, hosted by the Museum of Fine Arts and ELTE Faculty of Humanities as part of the Lendület framework. This event was, of course, aligned with the theme of the exhibition.

The temporary exhibition will be open to visitors at the Museum of Fine Arts until February 2, 2025.

Photo: Zoltán Niederreiter

Mesopotamia Exhibition

Mesopotamia Exhibition

Babylon

Babylon

0

/

0

0

/

0